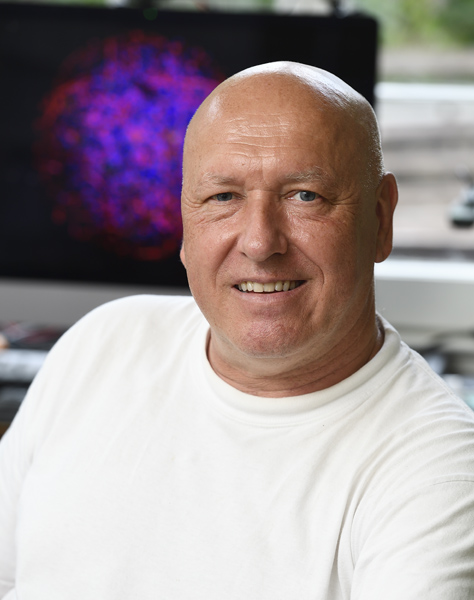

Pr. Thomas Hartung

One of the world's leading specialists in non-animal research

SES109 — June 2023Professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Prof. Thomas Hartung, before moving to the United States in 2009, was head of the European Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods of the European Commission (EURL-ECVAM) from 2002 to 2008. Throughout his career, Thomas Hartung has also received numerous honors and awards. Since 1993 and throughout his career, Thomas Hartung has received numerous awards, such as the US Society of Toxicology Enhancement of Animal Welfare Award in 2006, the Russell & Burch Award from the Humane Society of the US in 2009, 2020 the Ursula Händel Animal Welfare Prize for Alternative Methods to Animal Testing by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) and the Merit Award by EuroTox 2020/2021. An internationally renowned scientist, generous and productive, Prof. Hartung has thus carried out significant publication work with 640 articles cited more than 43,000 times.

Image credit : Pr. Thomas Hartung

Comité Pro Anima : For our readers, can you introduce yourself, explain what led you to research and teaching and more particularly to your interest in the field of toxicology and the challenges of alternative testing and methods to animal experiment ?

I love animals but I chose the wrong job for this – pharmacology and toxicology. Here, traditionally many animals are used. So, starting with my master thesis 1988, I worked on alternatives to animals in this field. At the time, cell culture was just beginning to become a more common tool with an industrial infrastructure for consumables, and computers were not powerful enough to allow major substitution. In pharmacology and in general in most science, there is a competition of ideas and methods change quickly. Most scientific papers are nowadays not using animals. However, regulatory toxicology is a different case. The animal tests, which are used here or are just right now being replaced, have been introduced when I was not yet born or in kindergarten. Since they are such a stable target, they are quite ideal for a one-by-one replacement. So, while in most science, we will never know what the consequence of using a non-animal method will change, when it is about the traditional animal tests for safety, we do.

Comité Pro Anima : For which experience / For which position did you have the most results ? What experience / what position among all those you have held has given you the most satisfaction, whether in scientific terms and/or in terms of regulation ?

I love my work, every day of the year. The first academic phase in Konstanz, I was still a lot in the lab myself and developed alternative tests for liver inflammation and pyrogen testing. In the European Commission from 2002 – 2009, I learned about the interplay of science and policy and enjoyed the work on large scale with many researchers. I was able to influence some legislation such as the chemical legislation REACH and the validation studies initiated led so far to 20 OECD test guidelines and two guidance documents as well as one European & US Pharmacopoeia monograph. Since 2019, at Johns Hopkins, I have the privilege to work at a top university second to none with the most complete academic freedom. I think in all phases, I was able to shape the field, have an impact, and this is giving me most satisfaction.

Comité Pro Anima : In 2021, the EDQM announced the decision to remove rabbit pyrogen testing from the European Pharmacopoeia. You were at the origin of the alternative MAT test recognized by the European Pharmacopoeia since 2009, a test which in 2001 received the Business Innovation Award from the Lake Constance region. Can you explain the particularity of your alternative MAT test ? Why is this test, its validation and admission into/by the European Pharmacopoeia of great importance ?

The idea of a pyrogen test based on the human fever reaction, what we now call Monocyte Activation Test, goes back to Charles Dinarello 1984 and Steve Poole in 1989. I invented a simpler variant 1995, which received its first award already in 1996 by the Doerenkamp-Zbinden-Foundation (of which I am now a proud vice-president). My most important contribution was probably that I did not just validate my own test but brought all developers of similar tests together and steered the validation study. Pyrogen testing used to be one of the most done animal experiments. In 2008, still 170,000 rabbits were used in Europe. To put this into perspective : This is about the number for all chemical or pesticide testing then, or before all bans and alternatives, the notorious Draize rabbit eye test used about 5,000 rabbits per year in Europe. So, while it took unacceptably long – 30 years – to get rid of the rabbit test, getting it down to 20,000 rabbits now and to zero in three years is a major accomplishment.

Comité Pro Anima : In your opinion, what are the main obstacles / blockages to the transition to non-animal research ? What action levers do you identify as the most relevant to overcoming these obstacles ? Could there be more in the near future ?

Most important, the value of animal studies is overestimated. Science is not good in self-critical evaluation. We will not write in our papers and applications “I use a mediocre test”…. It is always “state-of-the-art”. It takes a lot before a researcher turns against the tools used so far as this somewhat invalidates their earlier work. For most animal tests, we have no objective evaluation and where we have them, they are often shockingly bad. I also believe that for most areas of animal use, we have now equivalent and even better methods at hand. What it needs is change management, especially in the regulatory field.

Comité Pro Anima : Big Data and AI are part of your research interests. What possibility(s) would offer the meeting of AI with brain organoids ? In what respects would the meeting of these two fields be promising in your opinion ?

AI is the most disruptive technology I have ever seen. As chief editor of Frontiers in AI, I have the privilege to observe a lot of these changes first-hand. Already in 2018, we showed ourselves for 190,000 chemicals with toxicity classifications based on guideline animal studies, that we identified 87% correctly while these nine most used animal tests where only 81% reproducible. But again, it takes ages before this enormous potential animal saving is coming into application.

Organoids and organ-on-chip systems, together part of the so-called microphysiological systems (MPS), are the other disruptive technology in the life sciences. Based on human stem cells, they finally give us models of human organs and their interplay. We started a series of MPS World Summits and a society last year. In June, we bring this now to Berlin with expected 1,300 participants.

Most recently, we started combining the two disruptive technologies, in our case brain organoids with AI – we call this Organoid Intelligence (OI). These brain organoids have all the known machinery for learning and memory. Combining them through electrophysiology, i.e., giving them input, output and feedback about the consequences of their output, we are developing models for neuroscience, drug development for diseases like autism and Alzheimer’s, tests for toxicants contributing to such diseases and some computer engineers hope to build better computers based on understanding the brain or even using such biological components. This exciting perspective is just going viral !